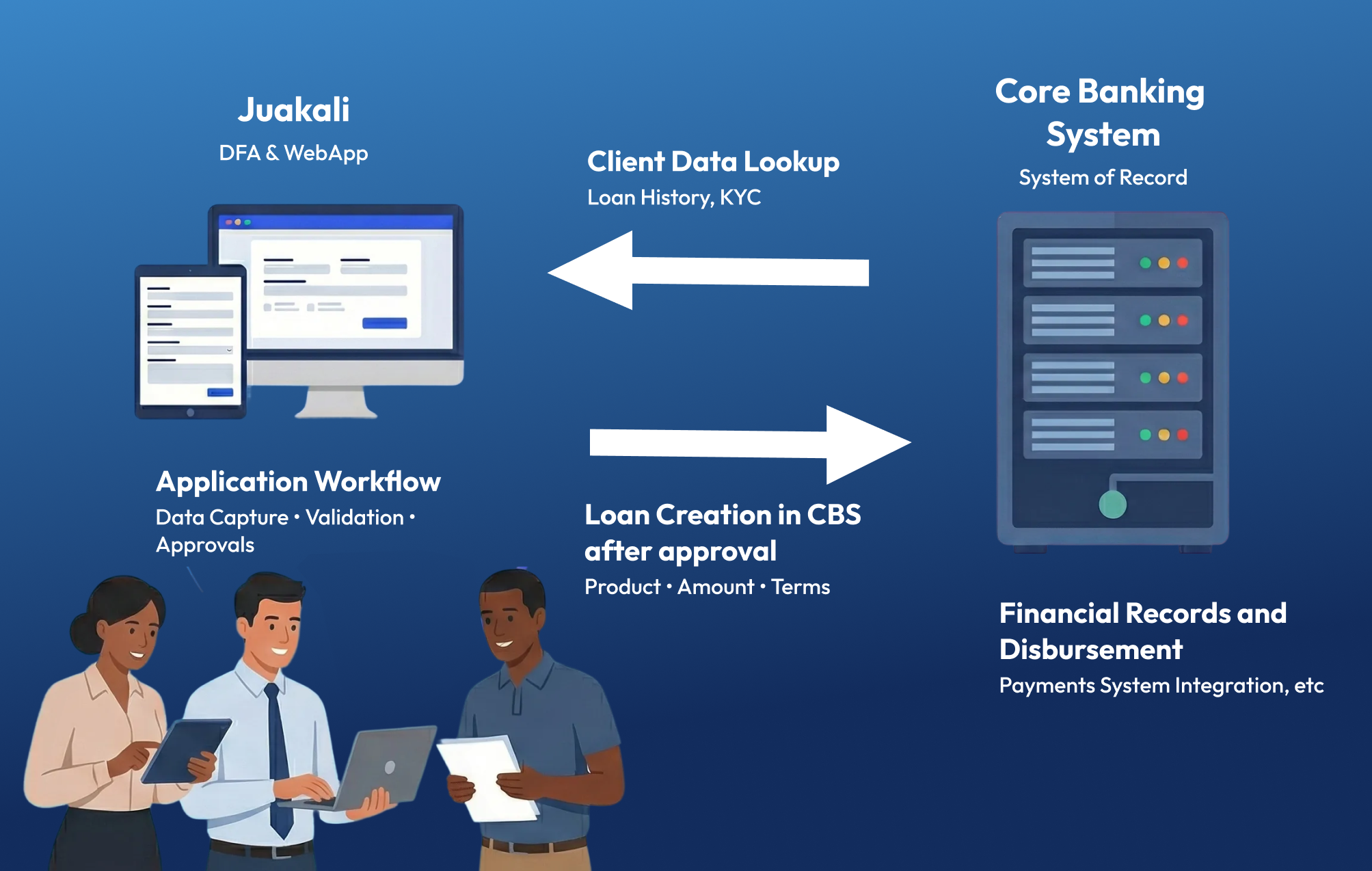

When a microfinance institution introduces Juakali, the core banking system does not disappear, and it does not move to the background. It stays exactly where it already is: at the center of the institution’s financial records.

What changes is how loans are originated.

Rather than forcing complex workflows, approvals, and supporting data into the CBS, Juakali is used to manage the process around the loan, while the CBS continues to do what it does best. This separation shows up very clearly once you walk through a real loan origination flow.

In general, the CBS remains the system of record for core data. Client identities, accounts, existing loans, balances, repayment schedules, and arrears all live there. That is where they belong.

Core banking systems are built for accounting accuracy, transactional integrity, and regulatory consistency. They are reliable, conservative systems by design.

What they are usually not designed for is storing evolving application data, enforcing multi-step approval processes across teams, or handling large amounts of contextual information such as household data, documents, photos, and field-level observations. Trying to push those responsibilities into the CBS often leads to brittle configurations and workarounds that are hard to maintain.

This is where Juakali comes in to handle that surrounding workflow, without undermining the role of the CBS.

A loan application begins in Juakali, typically with a field agent capturing application data on the DFA. At this point, the field agent captures the requested amount, product and tenor, loan purpose, household or business details, and any required documents or photos.

Nothing is written to the CBS at this stage.

That is a deliberate choice. Early-stage applications are incomplete by nature. Many will be revised, paused, or rejected. Allowing them into the core system too early creates noise and increases the risk of inconsistent data. By keeping applications in Juakali until they are approved, the CBS remains clean and authoritative.

However that doesn’t mean that the CBS isn’t used at this stage. If the applicant is an existing client, the CBS can be leveraged to retrieve core client information such as identity details and client status, existing loan information (including outstanding balances and arrears), and relevant repayment history.

This information is pulled directly to the DFA by the field agent, providing them with all the necessary context.

The retrieval also supports the KYC step; since client photos and identity data are already stored on the CBS from previous onboarding, this re-uses existing KYC data. Furthermore, Juakali’s facial recognition prevents any attempt at using someone else’s identity to access a loan.

This enriched data is immensely valuable, simplifying the loan review process for back-office staff who now have all the necessary information within the Juakali web app, eliminating application switching.

This approach ensures there is no duplicate data entry and no ambiguity about which system is the source of truth. Juakali displays what the CBS already knows and uses it to inform decisions, without modifying it.

For many institutions, these read-only lookups already deliver significant integration value by reducing manual checks, speeding up appraisals, and improving consistency with very little risk.

As the application progresses, Juakali applies workflow rules and validations. Required fields are enforced, documents are checked, and product-specific constraints are applied. Eligibility logic can reference CBS data, but the logic itself lives in Juakali.

At this point, the application is still not a loan in the CBS. It is a loan application, moving through a controlled process.

This distinction matters. It allows institutions to change workflows, approval thresholds, or validation rules without touching the core system. The CBS remains stable, while Juakali absorbs the operational complexity.

Approvals are handled entirely in Juakali.

This usually involves multiple approval levels, amount-based or product-based thresholds, role and branch permissions, and a full audit trail of who reviewed and approved what. Maker checker is enforced consistently at the workflow level, rather than relying on partial or uneven controls in the CBS.

Only applications that have passed all required approvals are allowed to move forward. Everything else stops in Juakali, where it can be reviewed, corrected, or rejected without side effects in the core system.

Only once a loan is fully approved does Juakali write back to the CBS.

The write-back payload is intentionally limited. It typically includes a client reference, the loan product identifier, the approved amount, the tenor and interest parameters, and the resulting loan status. At this point, the loan officially exists in the CBS and becomes part of the institution’s financial records.

Some institutions also trigger disbursement from Juakali. Others prefer to keep disbursement fully within the CBS. Both approaches are common. What matters is that write-back happens once, at a clearly defined moment, and only after all approvals are complete.

In production environments, Juakali is sometimes connected to the core banking system through a middleware or ESB layer. This is especially common when working with on-prem or older CBS platforms.

In those cases, middleware acts as a controlled interface between systems. It handles things like authentication, audit logging, retries, rate limiting, and the separation between test and production environments. It also reduces how tightly Juakali is coupled to a specific CBS implementation, which can make upgrades or system changes easier to manage over time.

For more modern, cloud-native core banking systems, this extra layer is often not required. These platforms typically provide well-designed APIs and built-in mechanisms for security, monitoring, and reliability. In such setups, Juakali can integrate directly with the CBS without adding unnecessary complexity.

Regardless of the technical setup, the institution remains responsible for its relationship with the CBS vendor. In practice, integrations work best when the CBS interface is documented, tested, and usable by the institution itself, without relying on ongoing vendor involvement.

Before integrating any core banking system, a few conditions need to be in place. The API must be documented and actively used by the institution itself. Ownership of the CBS relationship must be clearly internal, with the ability to test, monitor, and maintain the integration.

If an institution cannot reliably interact with its own CBS API, integrations tend to become fragile. In those cases, external support is usually required. Without internal ownership or sufficient external capacity, it is often better to postpone integration than to build something that cannot be sustained.

What this loan origination flow shows is a clear division of responsibilities between systems.

Juakali manages the operational process around the loan: data capture, validations, approvals, and audit trails. The core banking system remains the system of record for financial data and is updated only once the loan is approved and ready to exist as a financial object.

This approach keeps the core system clean and stable, avoids premature or inconsistent data, and allows institutions to change how loans are originated without reconfiguring their CBS. Workflow logic can evolve, approval structures can change, and field processes can adapt, while the core system continues to do what it is designed for.